Reprinted from The Austin Chronicle May 24, 1991

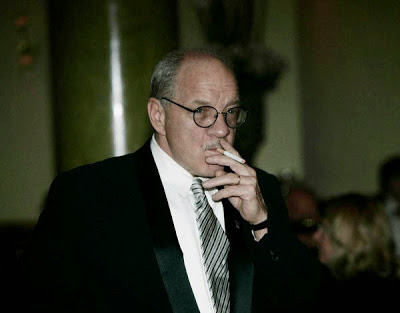

PAUL SCHRADER: ARE YOU TALKING TO ME? INTERVIEW BY RICK LINKLATER

When the Chronicle asked if I’d be interested in doing a phone interview with Paul Schrader, I jumped at the chance. As the writer of some of the most important films in the last 15 years, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, The Last Temptation of Christ, among others, Schrader is a screenwriter with few equals. As a director, his credits are a list of some of this country’s most consistently intelligent, provoking, and downright unnerving films: Blue Collar, Hardcore, American Gigolo, Cat People, Mishima, Light of Day, Patty Hearst, and most recently, the eerie and beautiful Comfort of Strangers, which opened here last week. Scripted by Harold Pinter from the novel by Ian McEwan, the film concerns a young English couple, Mary and Colin (Natasha Richardson and Rupert Everett); who while tourists in Venice fall under the influence of an older couple, Robert and Caroline (Christopher Walken, Helen Mirren). With five pages of notes, I had eager questions and comments on virtually every film he had ever been involved in. I imagined a long conversation that would cover everything, but on this day, he was very busy preparing to shoot his new film, Light Sleeper, which features Willem Dafoe and Susan Sarandon and begins rolling in New York next week.

AC: When I first heard what your new film was about, it didn’t sound like your typical kind of material. It was only after seeing it that I realized you’d made your kind of film.

PS: This is very British, very Harold Pinter. A four-character piece and the only movie I’ve done where I didn’t make a choice as to which character I was in favor of … there’s no protagonist. All four characters are equally complex, though Walken is sort of the bad guy.

AC: But I think these are very much your type of characters. Mary and Colin, as a couple, are fighting a certain emptiness in themselves and ultimately aren’t in control of their lives, which could be said of many of your main characters.

PS: What I’m most proud of with the film is that when I came to it there were already two artists involved with strong and distinct signatures (Pinter and McEwan). Each has a body of work unlike anyone else’s. One of my goals in the directing of it was to not obliterate their signatures. Both Ian and Harold really like the film and still feel very possessorly of it and that made me feel very good.

AC: It seemed like a fun film for you both visually and narratively…

PS: It helps to have four good actors. I didn’t have to worry about coverage as much or whether they could hit their marks with all the moving camera shots and still give the right performance. It makes life so much easier.

AC: It’s a perfect cast: Walken is becoming some sort of national treasure.

PS: They were all there in service of the text, not at the service of some public relations agency.

AC: It’s a strong story, but it’s also one of your most interesting films visually. It has a quality that leaves plenty of room for that “other” thing that gets everybody thinking.

PS: This movie doesn’t give itself up in the first 15 minutes: it holds a lot back, which is why it’s an art house kind of movie for a more intellectual audience. Most American films tell the audience what they’re going to do, do it, and tell them what they did, and of course never ask them for an opinion. There is a lot of this movie that simply doesn’t give itself to the viewer, the viewer has to come to conclusions, right or wrong, about what’s going on.

AC: It has an almost dream-state logic, sort of like Cat People.

PS: Maybe a lot of that comes from the dolly movement and never coming back to the same angle twice: so it’s always a sort of new film. And Venice adds a certain ambience.

AC: You seem to be working less and less under the studios. To make the films you want to make, do you see yourself thinking in terms of these kinds of international productions?

PS: Yes. This new film (Light Sleeper) was originally going to be financed by the French, but a the last minute, as they were dragging their feet, I managed to pull an American rabbit out of a hat from a company that originally turned it down.

AC: If you were starting out today, would you still go to Los Angeles?

PS: I think you still need to bring in in L.A. — the home of international cinema. Hollywood cinema is international cinema. As soon as anyone gets big in international cinema, they come to Hollywood to make movies. They don’t make international movies in Europe.

AC: What do you feel about the “movie brat” generation you came up with — that first wave of directors out of film schools who came to prominence in the ’70s?

PS: I think a lot of the people we came up with have become a little disappointing as they reached middle age. The fire went out. I escaped that inevitable “rusting of the sabre” because, at a critical juncture, I escaped and now I live in New York. But, directors like Scorsese, Coppola, Phil Kaufman, Lynch are every bit out there. They should be — succeed or fail. The others… if you start making kid’s movies in your twenties, if you keep trying to make those same kid’s movies in your forties, it gets a little hard because not only do you not know the kids anymore, you’re also fighting the demographics of your own sensibilities.

AC: In interviews I’ve read, you always seem to have a very healthy, non-bitter attitude toward not only the system, but to the whole collaborative process that is film making. You’re the only person who comes to mind that has not only written and directed his own films, but also written for others and directed from other’s scripts.

PS: I’ve been fortunate in that I’ve always finagled a way to get things I really cared about done. I really wanted to see Last Temptation and Mishima made and got them made. This latest project, I started financing on my own, after it was turned down by 27 people. I’m over $300,000 into the picture, which is everything I have, so: (laughs) it gets a little chancy. That’s Coppola’s theory too — just pretend you’re making a movie… if you pretend long enough, someone will believe you.

AC: Why is Light Sleeper a difficult film to finance?

PS: All the heroes are drug dealers.

AC: Isn’t that somewhat marketable? What about New Jack City?

PS: They think of that as more of a Black action picture. And the protagonists are the cops. In Light Sleeper, the protagonists are the drug dealers and there aren’t any cops. It’s the mid-life crisis of a drug runner.

AC: Sounds great.

PS: It’s this perverse thing: (almost sinister laughter) I try to find the least sympathetic character in Society, the most socially despicable, be it an assassin (Taxi Driver), a male prostitute (American Gigolo), a drug runner, and I say, “Here is our hero.”

AC: Taxi Driver is such an important film to me personally and I’ve always identified with Travis so clearly it’s hard to have much perspective on how messed-up he really is. I watched it recently with the sound off just to try to get a little distance and the movie now seems, along with Psycho, one of the most perverse tricks in cinema history. He’s such a sympathetic, lonely character — who couldn’t relate to that? Soon we realize we’re in the head of, and rooting for, a moralizing psychotic. But it does best what cinema can do naturally, pull in an audience that is longing for someone to identify with.

PS: The trick is to get the audience deep enough in and by the time they realize they don’t want to identify with the protagonist, they’re interested in how it’s going to turn out. One of the things I said to Scorsese at the time is that there can not a scene that is not from the Taxi Driver’s point of view. The minute you admit to the audience that there is another point of view in life, they will not like this guy. One of the mistakes Marty made with The King Of Comedy is that he showed you Jerry Lewis’ reality instead of only Rupert’s reality. Once you get out of Rupert’s skin, you judge him (both laugh).

AC: And Travis doesn’t have to be in New York City. He’s obviously not from there:

PS: It’s a hell of his own making. . .

Rick Linklater directed the locally made movie Slacker, set to open nationally on July 5.

Special thanks to Marjorie Baumgarten for tracking this piece down and to Kati Mellor for transcribing from a rough photocopy.

All Rights Reserved, Copyright Austin Chronicle Corporation.